What I didn’t know then: Wildfire displacement as a wheelchair using parent, by Alex Wegman

I’ve always understood that access and independence are fluid and mean different things for different people. What’s modified for my access might create barriers for another person, and what works for me in one environment or situation might not in another. I see it play out in my everyday life all the time. For example, the ramps on my house. I can’t get into my front door without them when I’m using my chair, but they’re significantly more difficult for me to use on foot than the single step down would be. Last year, I experienced the give and take of various kinds of access in a context I never had before: Natural disaster.

On August 18, 2020, my family left for our first overnight away from home since that March, when the shelter in place orders were issued. We planned a two-night camping trip with our pandemic pod and drove four and a half hours into the Sierra National Forest, to Hume Lake, in our new-to-us, not yet converted Sprinter campervan-to-be. I use a wheelchair and Smart Drive pretty much full time, but was prepared to take only my big, heavy hiking chair, knowing I probably wouldn’t use my everyday chair at the campground. At the last second, my husband threw it in the van because we had extra room. With no cell service to speak of, we cooked, swam, kayaked, and basked in the change of scenery. I had a writing deadline, so the afternoon after we arrived, we drove to a camp across the lake rumored to sell access to wifi. We planned to connect so I could send my email, check out that side of the lake, and then head back to make dinner.

Everything we had in our possession when we found out about the fire

Blissfully unaware of the news I’d receive an hour later

The second I connected, my phone buzzed with what felt like a zillion ominous, vague texts.

“Are you okay? We’re worried.”

“Alex, I’m so sorry, please let us know if you need anything.”

It took a few minutes to parse it all, but eventually we figured out there was a wildfire raging where we lived and the whole town had been evacuated with an hour’s notice about twelve hours after we left to camp. There was no official information to be found; save for the daily press conference given by the fire and sheriff’s departments, local news, neighborhood Facebook groups, and group texts with neighbors, with all their uncertainty, speculation, and contradictions, were the closest we could get to eyes on the ground. In those first 72 hours, we were glued to our phones and saw everything from (incorrect) news that our entire neighborhood was leveled to images of dozens of fire trucks lining our little downtown main street. I always assumed there were official channels for disaster communication, but I was very wrong.

In addition to the extreme stress and fear associated with the high probability we’d lose our home, we had immediate practical needs. We’re a family of four, and at the time we had a one -year-old and a four-year-old. I’m a full-time parent and wheelchair user, and my husband, Bryan, has a full-time job. Unlike neighbors who’d had an hour to pack up what they could, we had left with supplies to camp in hot conditions for two nights, and that was it. We knew anecdotally that even if our home survived, it would probably need smoke remediation, and it would likely be weeks before CalFire cleared residents to return to our properties. We needed clothes, toiletries, toys for the kids, I desperately needed a Smart Drive, and we would have to deal with access tradeoffs no matter where we ended up.

There was chatter in our Facebook groups about FEMA and the Red Cross and what kinds of accommodations and assistance they could provide—there were hotel discount vouchers available at some base camps on certain days and school gymnasiums full of cots—and it became clear quickly there was no contingency plan whatsoever for disabled residents with needs for accessible transit, housing, or access to meds and medical equipment. Even accessing the few available supports required one to drive to a disaster base camp and stand in line at a tent.

We spent the first five nights in a hotel room with one queen bed, arranged by Bryan’s employer’s disaster response team. The fire had displaced over 77,000 residents, and Bay Area accommodations were packed. As someone at high risk for serious illness with COVID 19, my anxiety was high, and balancing that with the stress of the crisis at hand caused fatigue like I’ve never experienced before. Having to navigate hotel hallways with thick, soft carpet without the help of the Smart Drive and get into and out of a bed that was about a foot too high proved to be formidable challenges, but I got by.

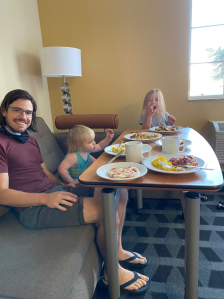

Breakfast in our little hotel room

We were able to move out of the hotel on August 25 and into the home of generous friends who went to visit family in Washington, partly to give us a place to stay and partly to escape the bad air quality. The house, two stories, with steps into the entrance and all bedrooms on the second floor, was a sweet relief from the squishy hotel carpets and skyscraper bed, but came with its own set of challenges. As the full-time caregiver of my kids, I found myself having to ask for help with what felt like _everything_. When my son needed a nap, Bryan had to break away from work to carry him upstairs. If my daughter got into mischief that involved the steps, Bryan had to intervene. I borrowed a Smart Drive from a friend so I could get around and keep up with the kids outside after both the manufacturer and Durable Medical Equipment (DME) provider failed to respond to my emails and calls about a loaner for my extenuating circumstances, but if I wanted to take the kids for a walk, I still needed help getting out of the house and then back in. While we were there, our house was confirmed still standing, and on September 3, we were cleared to go and look at our property. The house was covered in ash inside and out, and would need significant work before we could move back in.

Ash and soot on our deck and my ramp

After a couple weeks in the house, we moved to a yurt on another friend’s property. Before we moved in, he built a deck so I’d have level entry from the driveway, rather than having to climb down a hill and then up a set of stairs, and the situation inside was easier for me to navigate than the house. Basically, a large studio apartment. At the yurt, which is situated on a little mountaintop in the Santa Cruz Mountains, about an hour north of our house, the challenges were primarily outdoors, where the terrain was bumpy and steep. The main house, where we did our laundry, was up a hill I couldn’t manage without help, and the wifi connection in the yurt was poor so I couldn’t communicate much with the outside world. I felt isolated and useless when it came to anything outside our dwelling, and frequently had to call Bryan away from work to help with kid problems when they were out of my reach or to help me with things like laundry and getting around the property. By the time we moved home on October 31, my self-esteem was at an all-time low. It had been two and a half months since I’d been in a living situation in which I could function like I was used to, and despite my overwhelming gratitude for the generosity and thoughtfulness of our friends, the relief of being back in the space I’ve so carefully crafted for my use washed over me like a tidal wave.

The yurt

As I write, I’m struck by how conflicted I feel about sharing the access challenges I dealt with during our displacement—we were incredibly fortunate to not have lost our home. We had damage to repair, but didn’t have to start from scratch, and most of our belongings were salvageable. The few things that weren’t were replaced by insurance. We have amazing friends who provided us with everything from clothes and toys to meals and babysitting to shelter, and one even modified his property to make it easier for me to use. But there’s no pretending that any of it was easy, and the repeated displays of ambivalence to the wellbeing of disabled evacuees were sobering and painful.

We knew when we moved to the mountains that it’s a high fire risk area, but we discovered like many other evacuees that it’s difficult to imagine having to flee, and we didn’t have a plan. Here are my practical disability-related emergency prep tips:

– Take inventory of your belongings for insurance purposes — we did not have this, and it was incredibly stressful to think about how we’d handle replacing our stuff if we never laid eyes on it again. Especially my wheelchairs, crutches, and spare parts I’ve accumulated for each of them.

– Make a list of the things you’d take with you if you had ten minutes to flee and note their locations in your home — we weren’t home and didn’t have the chance, but on reflection, realize we would probably have panicked and not remembered what to take, especially since I can’t move very quickly and there’s a lot I can’t reach or carry.

– Avoid leaving home for extended periods during risky seasons without the things you need to survive for up to a week — we almost went camping without my everyday wheelchair and we did leave the Smart Drive behind. Never again. I don’t even go for curbside pickup errands without both of them anymore.

– Keep spare meds and equipment in your car or a friend or family member’s house (geographically distanced from your home) if possible. If not, inquire with your providers about obtaining them in the case of emergency and write out detailed instructions for yourself.

– Make a document detailing necessary physical accommodations. As we weighed our options for shelter, it was stressful and difficult to create criteria on the fly. A document would have made that much easier.

– Know your local Regional Center and if they have anyone you can contact in a crisis. I wasn’t connected with mine, and the idea of tracking down contacts and explaining my situation to new people was totally overwhelming, so I didn’t.

Emergencies can strike at any time, and we may have no choice but to adapt and do without, but we can take proactive steps to lessen our own suffering and preserve our dignity. It’s my sincere desire to never go through anything like last summer’s CZU wildfire again, but I know if I do, I’ll be much better prepared to care for myself and my family physically and emotionally.

Alex Wegman and her family of four live in California

Did you like this article? Are there other topics you’d like to see us publish on? Do you want to apply to be a guest blogger? Please take our quick, 3-question survey and let us know what you think!

Take Survey: http://survey.constantcontact.com/survey/a07eg1rmj5jjrasph9l/start